Newton, British Columbia — A B.C. Supreme Court judge granted an RCMP application to continue to hold onto clothing that was seized from a "person of interest" following the 1993 homicide of Dorothy Britton, 80, in Newton, in light of advances in DNA forensic technology.

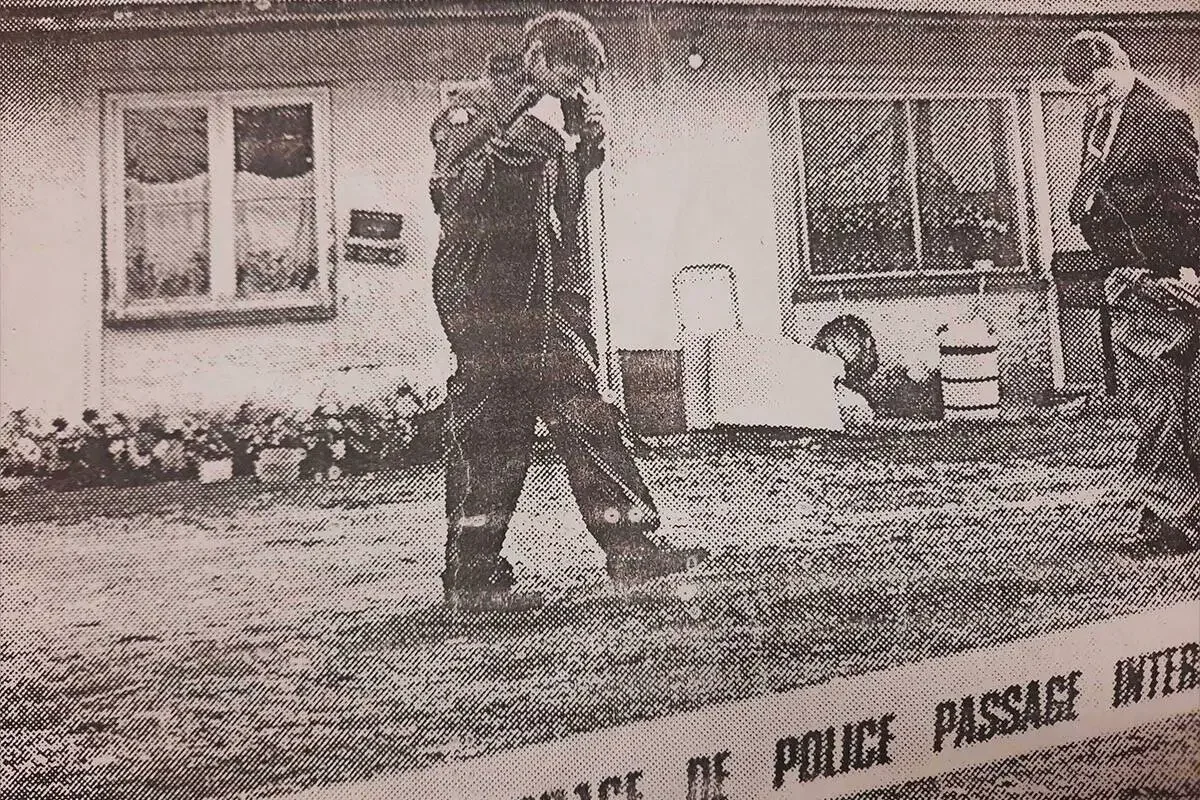

Police were called to the Dorothy Greer Britton's house at about 8:30 p.m. Tuesday, March 30, 1993, after her neighbours noticed she hadn't brought in her morning newspaper.

Britton was stabbed five times in the chest in her tiny bungalow next to the Bonanza Motel, where she lived with her two pet dogs, birds and a few cats. A knife was found at the scene.

Police found her body on her kitchen floor just inside the door, lying in a small pool of blood. Her television was still on and – something unusual for the elderly lady – the floral curtains in her window were drawn. A garden table was carefully arranged in her backyard a few paces away, as if awaiting an afternoon tea party.

The RCMP is allowed to keep "bloodied clothing" seized from a person of interest in a homicide investigation, with a judge saying it is possible further examination could lead to a break in the case.

"The decedent had been stabbed numerous times and had bruising to her neck. There was a blood-covered knife blade from a paring knife located across the top of her body," Justice John S. Harvey wrote.

"The affidavit material brought before me sets out considerable advances made in DNA forensic technology since testing was performed in the 1990s and since last tested in 2008," Harvey noted.

Harvey noted that on the day after Britton died a person of interest was interviewed by police and acknowleged that he helped her pick up her cheques and then took a cab with her to Money Mart to cash them.

A forensic analysis of the beer cans found in Britton's room yielded fingerprints that were identified as belonging to a person only identified by the initials "S.O.," who was also a resident of the Bonanza Hotel.

Police interviewed S.O., who told them he had been with Britton the day before her body was found, going with her to cash her cheques and to buy the booze at a BC Liquor Store, the court heard.

"S.O. has an extensive criminal past including crimes of violence," Harvey wrote.

A search of S.O's hotel room resulted in the police seizing four jackets and one pair of shoes. A forensic analysis of the items found blood on one jacket and the shoes, according to Harvey.

"Analysis of the blood samples, collectively, indicated the quality and quantity were incapable of providing DNA typing patterns. Further DNA testing was performed on the samples in 1994, which indicated the presence of human DNA, but in insufficient quantity or quality for the purposes of analysis," the judge wrote.

In 2006, the case was reviewed by the Surrey Unsolved Homicide Unit. As part of that review, the clothing was sent for further testing, and Harvey noted that scientific advances meant that the blood found on one of the jackets was determined to have come from three separate people and "both male and female DNA was present."

While the possibility that the blood came from either S.O. or Britton was not eliminated, "nothing further emerged linking S.O. to the homicide," Harvey's decision said.

"The investigation stopped in 2009, but again was never concluded. Other historical homicides took on priority and the priority of this particular homicide diminished," he added.

In 2020, the case was reassigned to the Serious Crime Unit for review.Soon after the review began, investigators found that the application to detain the items expired in June of 1993. They were then transferred to a "secure facility" and no further testing was carried out.

In order to further test the items, Harvey said the court would have to grant an order to keep them in the custody of the RCMP.

In support of the application, the RCMP submitted affidavits that outlined plans for future forensic examination of the items and described how advances in testing may enable them to get more conclusive results than were available in the past.

In granting the order to keep the clothing for one year, Harvey said "the retention of the items sought to be 'further detained' are clearly essential to the ongoing investigation and, in my view, the further detention is in the interests of justice."

However, the decision also noted that the ongoing detention and testing of the evidence after the expiry of the initial order could be an issue if the case ever goes to trial.