Grew up in Manitoba and moved to Lethbridge. I love the city and the surrounding area, the winters are wonderfully mild and the summers are lovely. As others have said most of the crime is small stuff, if you're really worried about it you could look into Coaldale or Coalhurst as well, both are pretty close to the city.

Files ➲ Saskatchewan

Location: Manitou Lake, Saskatchewan

File: The Disappearance of Bradley James Wiesner

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

Location: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

File: Unsolved Homicide of Anthony Gunn

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Read The File

Location: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

File: Domestic Bliss Was Shattered on July 8

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Read The File

Location: Regina, Saskatchewan

File: Disappearance of Gary Percival

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

Read The File

Location: LaRonge, Saskatchewan

File: James Brady And Absolom Halkett: The Prospectors Who Vanished

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

Read The File

Location: Regina, Saskatchewan

File: Family, RCMP Hope Podcast Helps Solve The Case Of Misha Pavelick

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Mercus N.

Read The File

Location: Maple Creek, Saskatchewan

File: Saskatchewan Community Looking for Byron Watson

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Read The File

Canada's unsolved case files sorted by location

Bradley James Wiesner

Bradley James Wiesner

Last seen swimming towards the boat

UCF #104200202Location: Manitou Lake, Saskatchewan

File: The Disappearance of Bradley James Wiesner

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

On September 17, 1995, Bradley Wiesner, was last seen at approximately 8:00 p.m. Wiesner had been on an island with other individuals on Manitou Lake, south of Neilburg, SK, when the boat they were using started floating away from shore.

Wiesner was last seen swimming towards the boat, however, he disappeared in the darkness. Extensive air, diver and water searches failed to locate him.

If you have any information regarding the disappearance of Bradley James WIESNER please contact one of the following agencies: F Division RCMP Historical Case Unit (SACP) at (639) 625-4111 or Toll free 1-833-502-6861 / saskmissingpersons@rcmp-grc.gc.ca Or Crimestoppers: 1-800-222-TIPS (8477).

Wiesner was last seen swimming towards the boat, however, he disappeared in the darkness. Extensive air, diver and water searches failed to locate him.

If you have any information regarding the disappearance of Bradley James WIESNER please contact one of the following agencies: F Division RCMP Historical Case Unit (SACP) at (639) 625-4111 or Toll free 1-833-502-6861 / saskmissingpersons@rcmp-grc.gc.ca Or Crimestoppers: 1-800-222-TIPS (8477).

Anthony Gunn

Anthony Gunn

Found lying in a pool of blood

UCF #104200130Location: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

File: Unsolved Homicide of Anthony Gunn

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Darren Greschuk

Darren Greschuk

Shot in chest through the door

UCF #104200139Location: Saskatoon, Saskatchewan

File: Domestic Bliss Was Shattered on July 8

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Gary Percival

Gary Percival

Last Seen in Regina, SK

UCF #104200184Location: Regina, Saskatchewan

File: Disappearance of Gary Percival

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

James Brady and Absolom Halkett

James Brady and Absolom Halkett

The Prospectors Who Vanished

UCF #104200226Location: LaRonge, Saskatchewan

File: James Brady And Absolom Halkett: The Prospectors Who Vanished

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Brenton M.

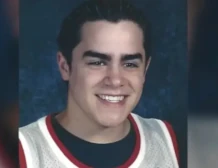

Misha Pavelick

Misha Pavelick

Stabbed to death at a graduation party

UCF #104200235Location: Regina, Saskatchewan

File: Family, RCMP Hope Podcast Helps Solve The Case Of Misha Pavelick

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Mercus N.

Byron Watson

Byron Watson

Left his home in the community

UCF #104200245Location: Maple Creek, Saskatchewan

File: Saskatchewan Community Looking for Byron Watson

Status: UNSOLVED

Contributor: Ryan A.

Jeffrey Dupres told his mother he was going with his five-year-old friend to play next-door at his house. About 20 minutes later, the friend showed up looking for him.

Featured for 16 days

Our work goes beyond data collection and is independent from Government and Institutional funding. Your support is critical in making this possible.

The 1980 murder of Kirk Knight; the 1982 murder of 31-year-old Marlene Sweet and her 7-year-old son Jason; the 2003 killings of 30-year-old Debilleanne "Dee Dee" Williamson and her son 5-year-old Brandon "Xavier" Rucker.

Windsor, Ontario